Indian Postcolonial Architecture - The Style of a New Era

- up2198805

- Apr 25

- 6 min read

Updated: May 20

1947 marked the beginning of a new era for India. British colonial rule is generally considered to have started after the Battle of Plassey in 1757 (Blackwell, 2008), and after 200 years of this, the country was finally able to govern itself without having to demand change from a colonial empire. During British colonial rule, Britain showed huge disregard for the culture and traditions of India. In fact, the 1857 rebellion/mutiny by Indian soldiers partially in response to the attempt to force “the use of Western technologies - the railroad and telegraph - upon a highly traditional society” (Blackwell, 2008), the fear of forced conversions to Christianity, disregard for the traditions of Muslim and Hindu people, the manufactured ubiquity of the English language in schools and courts, and the East India Trading Company’s attempts to take over states when their princes died without heirs. This insidious control of India continued past the mutiny, as the British government took over direct rule of India from the EITC, and continued to use India as a way to generate profit for the British Empire (Blackwell, 2008). While Britain controlled the politics and government of India, it is also important to note the role that they played in constructing and altering the country’s culture and design, as British influence led to European/British styles of architecture being heralded as more sophisticated or desirable than vernacular or local architecture.

Prior to its independence, churches in India were typically constructed in styles that were popular in Europe (and particularly Britain) at the time. For example, St Philomena’s Church takes a lot of inspiration from Gothic Revival architecture - the imposing spires, pointed arches, stained glass window, and intricate ornamentation cement it clearly in the Gothic canon. Additionally, All Saints Cathedral in Allahabad merges Victorian architecture with Gothic design. Similarly to St Philomena’s Church, the building is constructed with stained glass, a repeated pattern of arches, spires, and flying buttresses adorning the exterior walls (Dayall, 2024).

While these buildings are well constructed and contain beautiful design elements, this must be balanced with the fact that these designs were forced upon India’s cultural landscape as a method of cementing the supposed superiority of Western design. With 200 years of British colonial rule denying Indian people the right to rule their own country, it is important to note that a lot of larger, state-sanctioned activities (such as constructions of large buildings like churches) would have been controlled by those in power, and as such reflect a bias towards designs that would continue to champion British design sensibilities within India. 1947 marked the first time in centuries that the people of India were able to govern themselves, and naturally, this celebration of independence impacted far more areas of life than just politics.

One manifestation of India’s celebration of independence can be seen in the flourishing of post-colonial architecture in the later 1900s. When discussing Indian postcolonial architecture, Harshal Shinde asks “can architecture be a vessel for cultural memory while simultaneously embracing modernity without capitulating to borrowed idioms?” (Shinde, 2025), considering how Indian architecture could differentiate itself and innovate while still incorporating pieces of the cultural landscape of India and Indian design. Shinde concludes his post by explaining that he feels post-colonial Indian architecture is an “unresolved question” that still needs to take time to understand how it is going to weave together modern and traditional architecture to create a style unique and accurate to the aspirations of Indian design. As Arata Isozaki expressed, “architectural discourse demands that we view buildings as events and not simply as inert objects” (Al Dweik), demonstrating the importance of understanding the context around architecture and not just its physical form. With this framework, it feels most accurate to examine mid-1900s Indian postcolonial architecture as a moment in time that reflects a desire to distance itself from colonial rule and embrace a clear independence and exciting possibility of the future.

One interesting example of Indian postcolonial architecture is the National Cooperative Development Corporation building in New Delhi, India which merges elements of traditional and modern architecture to create a building that is unique and distinct in the landscape. Architect Kuldip Singh designed the building while inspired by the entrance towers of Gopuram (Dogan, 2023), and this influence can be seen in the stepped design that adorns the exterior and creates a narrowing effect towards the top of the building. The larger windows placed in the centre of each wall is also a design choice inspired by the Gopuram entrance towers. This inspiration from religious and historical architecture is then merged with the materials associated with the modernist movement, namely concrete and glass, forgoing the expressive and detailed ornamentation of the Gopuram entrance towers for a more minimalist and geometric facade. This combination honours both facets of inspiration and combines them in a way that allows them to compliment each other in a unique way steeped in both history and innovation.

Another area of Indian post-colonial architecture that has garnered a lot of attention are the churches of Kerala, Southern India. Photographer Stefanie Zoche describes the unique visual style of these churches as being due to a desire to “differentiate itself from the historical colonial building style” by combining modernism, an “effusively sculptural formal language”, a “use of intense colour”, and Christian symbols incorporated into “a three-dimensional, monumental construction design” (Walsh, 2018).

The 3D element is immediately visible as crosses, bibles, and stars adorn the front facade of the buildings. The bright colour palettes used make each one distinct from not only its surroundings, but the other unique churches. The style exudes the atmosphere of independence and experimentation, disregarding the components of Gothic or colonial architecture that were previously used to construct churches, in favour of the designers behind each church choosing to define the appearance of religion for themselves. The result is a collection of bold, bright buildings using warm colours, intricate and exciting shapes, and visually interesting patterns and rhythms to redefine the face of religion in Kerala.

Post-colonial architecture is one clear method for a country to express its “desires for self-representation” and commitment to “postcolonial political and cultural decolonization”. (Stierli & Pieris, 2022). The built environment is one way to assert culture in a way that makes an immediate and visible impact, and for a country like India (whose skyline had been forcibly filled with British colonial architecture for around 200 years), the step of redefining what Indian architecture is and could be was an important avenue for asserting and celebrating independence post-1947. Scholar Aplana Sharma once remarked that “modernism is the natural idiom… with which to chip away at the edifice of colonialism” (Stierli & Pieris, 2022), which is definitely an attitude that can be seen in Indian post-colonial architecture, as modernism is frequently merged with other design sensibilities such as vernacular architecture or bold experimentation to create something new that asserts itself independently in the landscape. Ultimately, these buildings serve as a fascinating expression of reasserting identity, power, and aspiration in a way that merges both modern and traditional to create a representation of India’s newfound freedom.

This post's thumbnail was inspired by Tritha's PaGLi (2021) album cover. Tritha describes the album as "the story of Indian woman's metamorphosis from traditions to breaking rules to find her freedom" (Tritha, 2021) which I feel mirrors the attitude of Indian postcolonial architecture, as both use their newfound freedom to explore and define their identities for themselves.

Sources:

Al Dweik, E. Postcolonial Architecture and Design. Rethinking The Future. https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/architectural-community/a11420-postcolonial-architecture-and-design/

Blackwell, F. (2008). The British Impact on India, 1700-1900. Education About Asia, Volume 13:2 (Fall 2008). https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/the-british-impact-on-india-1700-1900/

Dayall, R. (2024, January 9). 10 Splendid Churches in India Revered for Spirituality Across Eras. The Architect's Dairy. https://thearchitectsdiary.com/10-splendid-churches-in-india-revered-for-spirituality-across-eras/

Dogan, R. (2023, August 30). Post-colonial Architecture: 8 notable examples in South Asia. Parametric Architecture. https://parametric-architecture.com/post-colonial-architecture-8-notable-examples-in-south-asia/?srsltid=AfmBOoq02XkfNavzpyp7JL2HW_BJ7h3uW4BWiXkpHkrWREETzM9vSM1r

Shinde, H. (2025, February). The Paradox of Postcolonial Indian Architecture. Shinde. https://shinde.co/the-paradox-of-postcolonial-indian-architecture

Stierli, M., & Pieris, A. (2022, February 16). An Introduction to The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947-1985. MoMA. https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/698

Tritha. (2021). PaGLi. Bandcamp. https://tritha.bandcamp.com/album/pagli

Walsh, N. P. (2018, August 20). The Wild Churches of Kerala, Southern India as Captured by Stefanie Zoche. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/900488/the-wild-churches-of-kerala-southern-india-as-captured-by-stefanie-zoche

Figures:

Figure 1 - Dayall, R. (2024, January 9). 10 Splendid Churches in India Revered for Spirituality Across Eras. The Architect's Dairy. https://thearchitectsdiary.com/10-splendid-churches-in-india-revered-for-spirituality-across-eras/

Figure 2 - Dayall, R. (2024, January 9). 10 Splendid Churches in India Revered for Spirituality Across Eras. The Architect's Dairy. https://thearchitectsdiary.com/10-splendid-churches-in-india-revered-for-spirituality-across-eras/

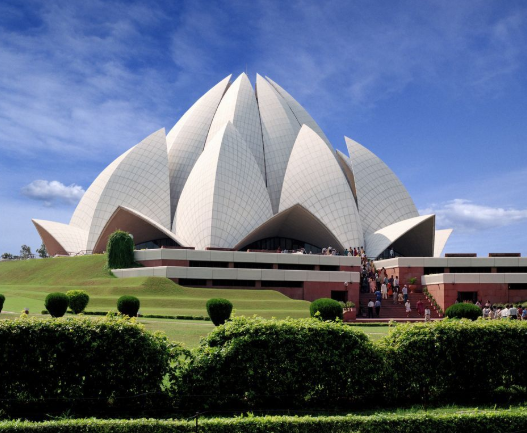

Figure 3 - Ayaz, S. (2024, January 18). 5 modern temples in India that redefine cultural architecture. Architectural Digest. https://www.architecturaldigest.in/story/5-temples-in-india-that-redefine-modern-architecture-lotus-temple-shiv-temple-stone-and-light-wadeshwar-tejorling-radiance-temple-sameep-padora-architects/

Figure 4 - Dogan, R. (2023, August 30). Post-colonial Architecture: 8 notable examples in South Asia. Parametric Architecture. https://parametric-architecture.com/post-colonial-architecture-8-notable-examples-in-south-asia/?srsltid=AfmBOoq02XkfNavzpyp7JL2HW_BJ7h3uW4BWiXkpHkrWREETzM9vSM1r

Figure 5 - Walsh, N. P. (2018, August 20). The Wild Churches of Kerala, Southern India as Captured by Stefanie Zoche. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/900488/the-wild-churches-of-kerala-southern-india-as-captured-by-stefanie-zoche

Figure 6 - Walsh, N. P. (2018, August 20). The Wild Churches of Kerala, Southern India as Captured by Stefanie Zoche. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/900488/the-wild-churches-of-kerala-southern-india-as-captured-by-stefanie-zoche

Figure 7 - Dogan, R. (2023, August 30). Post-colonial Architecture: 8 notable examples in South Asia. Parametric Architecture. https://parametric-architecture.com/post-colonial-architecture-8-notable-examples-in-south-asia/?srsltid=AfmBOoq02XkfNavzpyp7JL2HW_BJ7h3uW4BWiXkpHkrWREETzM9vSM1r

Comments